Two years ago I participated in the first polyglot conference in Budapest. My goal was to show how conflict management could be a wonderful career choice for people who speak more than one language. A video of that speech was eventually published on Youtube.

Unresolved Business

Even though I got some really good feedback after that speech I couldn’t shake the idea that something was missing. What else could be done to help multilingual people find a good fit in the job market? What could I do to help more of them be happier and more successful at work? After talking this conundrum over with a friend of mine, he encouraged me to reach out and do something new. I’ve described this exciting project in the video below:

If you haven’t yet, please take a few minutes to participate in this important study.

Lots of Good Data

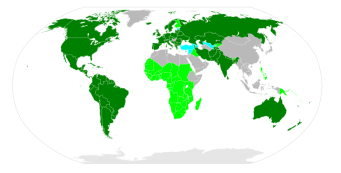

The first step is for us to get a real understanding of how bilingual and multilingual people are doing at work. We want to go beyond the personal experiences of one or two people—who work in one or two industries—and gather thousands of responses from all over the world. Not only is it important that you participate in the survey, it is also important that you encourage other bilingual and multilingual people to take the survey as well. Please share it on Facebook, Twitter, LinkedIn and on any other social media where you have an account.

The more responses we get, the more accurate our information will be. The more accurate the information we get, the more we will learn about what works and what doesn’t for multilingual people in the work place. Our goal is to get really specific. What languages are best to learn in France? Which jobs do polyglots enjoy the most in Brazil? Are polyglots more valued in the USA than they are in Russia? We can’t answer these questions unless we get enough responses from people in all of those places. Please, please, take this survey and share it with every bilingual and multilingual person you know.

Who Should Not Take This Survey?

Please don’t mistake my enthusiasm for a lack of scientific rigor. We don’t want just anyone’s responses. If you are under the age of eighteen then, I’m sorry, but I’m not asking you to participate. If you have any significant work experience it was likely gained illegally.

If all the Spanish you know is a handful of phrases like ¿Dónde está el baño? then I’m not asking you to participate. If all the German you know is Guten Tag. and Wieviel kostet das? then I’m not asking for your responses either. We are looking for people who are at least functional bilinguals.

Who Should Take This Survey?

Functional and perfect do not mean the same thing at all. If you can have an unscripted conversation with someone in a foreign language, for more than five minutes, then please take this survey. It doesn’t matter to me that you can’t speak without making mistakes. As long as the other person can understand you and you can understand him/her then please take this survey.

There may be some people who are thinking, Well, I don’t exactly love my job so maybe I should not take this survey. Nothing could be farther than the truth. By all means, if you have a job that you love then please take this survey. If you have a job that you hate then please take this survey. If you have a job you think is just okay then please take this survey.

Others may say, Well, I don’t really use my languages much at work, maybe I shouldn’t take this survey. Wrong again! One of the things we want to see is how many people out there are bilingual/multilingual but don’t use their languages at work. Whether you use your languages every day, only occasionally, or not at all, please take this survey. Even if you are retired we want to know about your career as a bilingual/multilingual person.

It’s true that, in isolation, your responses might not be particularly helpful to people. When compared with the responses of thousands of other people from all over the world, your responses—no matter how obvious or boring they may seem to you—will be helpful. They will be helpful because they are part of a greater truth.

Great Answers to Great Questions

Studies have been done that show whether or not people who know two languages make more money than people who know only one. Studies have also been done to show if a bilingual French speaker makes more money than a bilingual German speaker. While nice, these studies leave us asking more questions.

Do they make more money because of their language skills or because those people happen to work in a more lucrative job? We don’t know. They might make more money but do they like their jobs more than people who only know one language? We don’t know.

Does knowing English, Japanese or Chinese really open doors for you in the job market or is it your university degree? Is it something else entirely? Are languages like Danish, Zulu and Hindi not really worth learning—for professional reasons—or do some people benefit greatly in their careers because they know a less popular language? If they do then why are they benefitting so much?

These are the kinds of questions we want to have good, solid answers for. We want to eventually publish a study—based on empirical data—that will help companies see the value of multilingual people. We want our study to provide the basis for good career advice to bilingual people and polyglots from all over the world.

All our study needs now is you. Please take a few minutes and participate in this survey.

Filed under: Languages, Polyglots | Tagged: Languages, Polyglots, research | 2 Comments »